What is

Effective Altruism?

Effective altruism is a research field and practical community that aims to find the best ways to help others, and put them into practice.

salient domain was triggered too early. This is usually an indicator for some code in the plugin or theme running too early. Translations should be loaded at the init action or later. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.7.0.) in /home/efal/domains/effectivealtruism.mpbr.dev/public_html/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6131Effective altruism is a research field and practical community that aims to find the best ways to help others, and put them into practice.

Everyone wants to do good, but many ways of doing good are ineffective or even actively harmful. The EA movement arose from a desire to make sure that attempts to do good actually work.

We use careful reasoning and evidence to figure out how we can do the most good, and then we actually do it.

Following through on these ideas has helped the effective altruism community achieve a great deal.

We’ve prevented hundreds of thousands of deaths from neglected diseases by providing significant funding to organisations such as the Against Malaria Foundation.

We’ve founded institutes that research global priorities. For example, the Global Priorities Institute at the University of Oxford, which works to identify the most pressing problems and provides ideas for how we might solve them.

We’ve pushed for safer technological progress by supporting initiatives such as CHAI, a research community at UC Berkeley, that works to ensure new artificial intelligence technologies benefit humanity rather than posing unacceptable risks.

We’ve worked to improve animal welfare by supporting corporate campaigns and legal reforms that have freed more than 100 million hens from battery cages.

And much more!

Most of us really want to make a difference. We see suffering, injustice and death, and are moved to do something about it. But working out what that ‘something’ is, let alone actually doing it, can be a difficult and disheartening challenge.

Effective altruism is a response to this challenge. It is a research field, which uses high-quality evidence and careful reasoning to work out how to help others as much as possible. It is also a community of people taking these answers seriously, by focusing their efforts on the most promising solutions to the world’s most pressing problems.

History contains many examples of people who have had a huge positive impact on the world:

These people might seem like unrelatable heroes who were enormously brave, or skilled, or who just happened to be in the right place at the right time. But many ordinary people can also have a tremendous positive impact on the world, if they were to choose wisely.

This is such an astonishing fact that it’s hard to appreciate. Imagine if, one day, you see a burning building with a small child inside. You run into the blaze, pick up the child, and carry them to safety. You would be a hero. Now imagine that this happened to you every two years – you’d save dozens of lives over the course of your career.

This sounds like an odd world. But current evidence suggests it is the world that many people live in. If you earn a typical income in the Netherlands (or most other developed countries), and donate 10% of your earnings each year to GiveWell’s top charities, you could save dozens of lives.

In fact, the world appears to be even stranger. Donations aren’t the only way to help: many people have opportunities that look higher-impact than donating to global poverty charities. How? First, many talented people can have a greater impact by working directly on important problems than by donating. Second, other causes might prove even more important than global poverty and health, as we’ll discuss below.

In most areas of life, we understand that it’s important to base our decisions on evidence and reason rather than guesswork or a gut feeling. When you buy a phone, you will first read customer reviews to get the best deal. Certainly, you won’t buy a phone which costs 1,000 times more than an identical model.

Yet we are not always so discerning when we work on global problems.

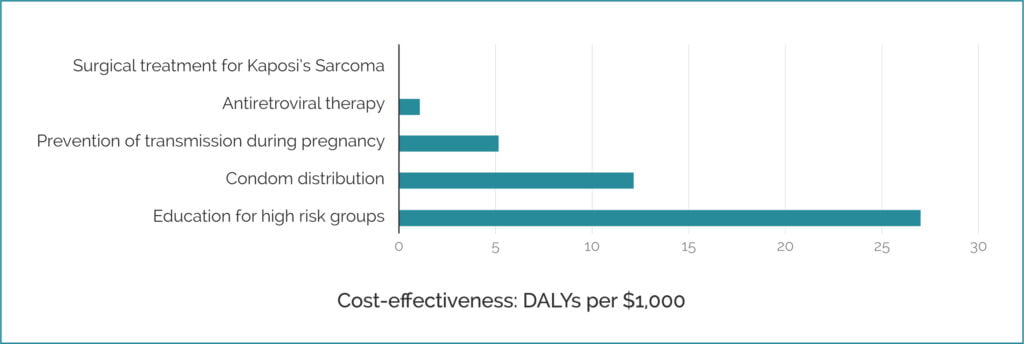

Below is a chart from an essay by Dr. Toby Ord, showing the number of years of healthy life you can save by donating $1,000 to a particular intervention to reduce the spread of HIV and AIDS. The chart shows figures for five different strategies (measured using DALYs).

The first intervention, surgical treatment, can’t even be seen on this scale, because it has such a small impact relative to other interventions. And the best strategy, educating high-risk groups, is estimated to be 1,400 times better than that (It’s possible that these estimates might be inaccurate, or might not capture all of the relevant effects. But it seems likely that there are still big differences between interventions.).

We suspect that the difference in intervention effectiveness is similarly large in other cause areas, though we don’t have as clear data as we do in global health. Why do we think this? Partly because most projects (in many domains for which we do have data) don’t appear to have a significant positive impact. And, more optimistically, because there appear to be some interventions which have an enormous impact. But without knowing which experts to trust, or which techniques to trust in your own research, it can be very hard to tell these apart.

Which interventions have the highest impact remains an important open question. Comparing different ways of doing good is difficult, both emotionally and practically. But these comparisons are vital to ensure we help others as much as we can.

The media often focuses on negative stories.

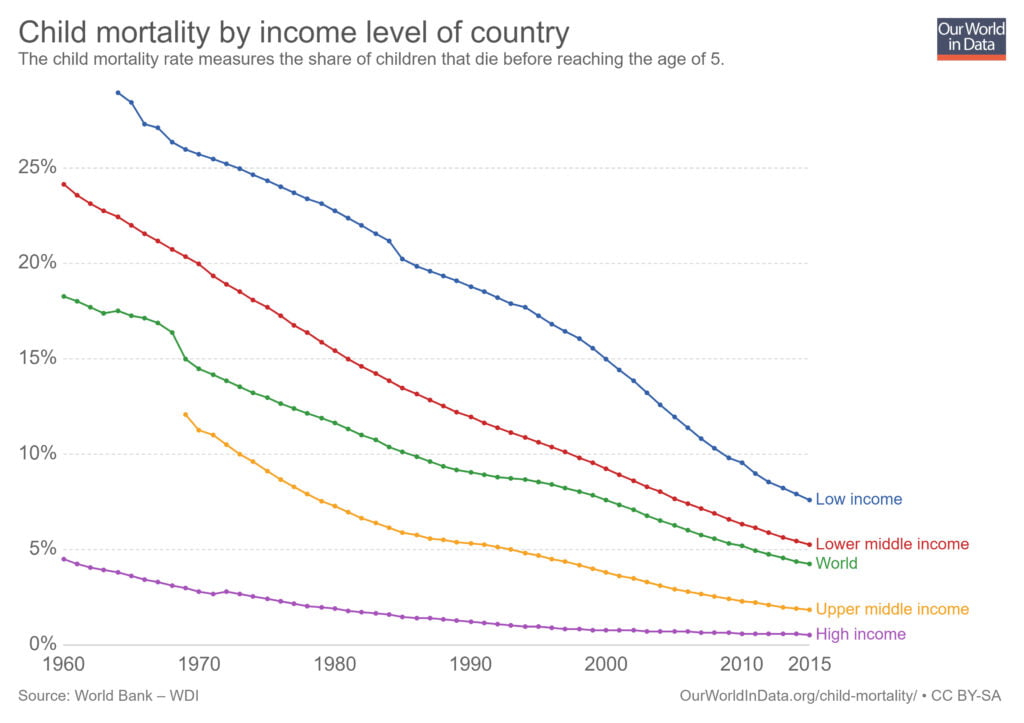

But in many ways, the world is getting better. Concerted efforts to improve the world have already had phenomenal success. Let’s consider just a few examples. The number of people living under the World Bank’s poverty line has more than halved since 1990. The Cold War saw thousands of nuclear weapons trained across the Atlantic, but we survived without a single nuclear strike. Over the last few centuries, we have criminalized slavery, dramatically decreased the oppression of women, and, in many countries, done a great deal to secure the rights and acceptance of people who are gay, bi, trans, or queer.

Nevertheless, many problems still remain. Around 700 million people live on less than $2 per day. Climate change and disruptive new technologies have the potential to harm billions of people in the future. Billions of animals, who may deserve serious moral concern, spend their lives suffering in factory farms. There are so many problems that we need to think carefully about which ones we should prioritize solving.

The cause that you choose to work on is a big factor in how much good you can do. If you choose a cause where it’s not possible to help very many people (or animals), or where there just aren’t any good ways to solve the relevant problems, you will significantly limit the amount of impact you can have.

On the other hand, if you choose a cause where you can provide a lot of help, using tested solutions, you may have an enormous impact. For instance, some attempts to reduce the suffering of animals appear to be incredibly effective. By thinking carefully and acting strategically, a small group of campaigners with limited budgets have helped to improve the living conditions of hundreds of millions of chickens who were suffering in US factory farms.

Many people are motivated to do good, but have already chosen a cause before they do any research. There are lots of reasons for this, such as personal experience with a problem, or having a friend who’s already raising money for a particular organization.

But if we choose a cause that simply happens to be salient to us, we may overlook the most important problems of our time. Given that most interventions seem to have low impact, we’re likely to focus on something that is not very impactful if we don’t pick carefully. We can do more good if we carefully consider many causes, rather than stopping at the first one we’re drawn to.

By remaining open to working on different causes, we also remain able to change course to where we can make the biggest difference, without unnecessarily restricting ourselves.

Then, how can we figure out which causes we should focus on?

Researchers have found the following framework to be useful. Working on a cause is likely to be highly impactful to the extent that the cause is:

On the basis of this reasoning, several cause areas appear especially likely to be highly impactful.

These areas are not set in stone. They simply represent best guesses about where we can have the most impact, given the evidence currently available. As new evidence comes to light that suggests different causes are more promising, we should consider working on those instead. It’s also worth keeping in mind that if we move to a better cause, even if we aren’t sure it’s the best cause, our impact can still be much larger than it might have been.

We’ll discuss three main areas: alleviating global poverty, improving animal welfare, and trying to influence the long-term future.

Diseases associated with extreme poverty, such as malaria and parasitic worms, kill millions of people every year. Poor nutrition in low-income countries can lead to cognitive impairment, birth defects, and growth stunting.

Much of this suffering can be prevented or mitigated with relative ease. Antimalarial bednets cost around $2.00 each. GiveWell, an independent charity evaluator, estimates that they can significantly reduce malaria rates. Even simply transferring money to people who are very poor is a relatively cost-effective way of helping people.

Improving health doesn’t just avert the direct suffering associated with sickness and death; it also allows people to participate more fully in education and work. Consequently, they earn more money and have more opportunities later in life.

The advent of industrialised agriculture means that billions of animals each year are kept in inhumane conditions on factory farms. Most have their lives ended prematurely when they are slaughtered for food. Advocates for their welfare argue that it is relatively cheap to reduce demand for factory-farmed meat, or to enact legislative changes that improve the welfare of farmed animals. Because of the huge numbers of animals involved, making progress on this issue could avert a very large amount of suffering.

Especially given the scale of the problem, animal welfare also seems extremely neglected. Only 3% of philanthropic funding in the US is split between the environment and animals, while 97% goes toward helping humans. And even within the funding spent on animal welfare, only about 1% goes towards farmed animals, despite the extreme suffering they endure.

If you want to know more about animal welfare as a collective priority, read this article about animal welfare.

Most of us care not just about this generation, but also about preserving the planet for future generations.

Because the future is so vast, the number of people who could exist in the future is probably many times greater than the number of people alive today. This suggests that it may be extremely important to ensure that life on Earth continues, and that people in the future have positive lives.

Of course, this idea might seem counterintuitive: we don’t often think about the lives of our great-grandchildren, let alone their great-grandchildren. But just as we shouldn’t ignore the plight of the global poor just because they live in a foreign country, we shouldn’t ignore future generations just because they are less visible.

Unfortunately, there are many ways that we could miss out on a very positive long-term future. Climate change and nuclear war are well-known threats to the long-term survival of our species. Many researchers believe that risks from emerging technologies, such as advanced artificial intelligence and designed pathogens, may be even more worrying. Of course, it’s hard to be sure exactly how technologies will develop, or the impact they will have. But it seems that these technologies have the potential to radically shape the course of progress over the centuries to come.

Because of the scale of the future, it seems likely that the best opportunities in this area will be even more impactful than those in the previous two cause areas.

And yet, existential risks stemming from new technologies have been surprisingly neglected. There are probably just a few hundred people in the world who work on risks from AI or engineered pathogens.

US households spend around 2% of their budgets on personal insurance, on average. If we were to spend a comparable percentage of global resources on addressing risks to civilization, there would be millions of people working on these problems, with a budget of trillions of dollars per year. But instead, we spend just a tiny fraction of that amount, even though such risks may become substantial in the decades to come.

If we value protection against unlikely but terrible outcomes individually, as our insurance coverage suggests we do, we should also value protection against terrible outcomes collectively. After all, a collective terrible outcome, like human extinction, is terrible for everyone individually, too. For this reason, it seems prudent for our civilization to spend more time and money mitigating existential risks.

There are many other promising causes that, while not currently the primary focuses of the effective altruism community, are plausible candidates for having a big impact. These include:

Of course, it’s likely that we have overlooked some very important causes. So one way to have a huge impact might be to find an excellent opportunity to do good that almost everyone else has missed. For this reason, global priorities research is another key cause area.

For most of us, a significant amount of our productive waking life — over 80,000 hours on average — is spent working. This is an enormous resource that can be used to make the world better. If you can increase your impact by just 1%, that’s equivalent to 800 hours of extra work.

80,000 Hours — named after the time you spend in your career — is a nonprofit organisation dedicated to helping people figure out in which careers they can do the most good.

First, you need to consider which problem you should focus on. 80,000 Hours has many suggestions for problems where one person can make a substantial impact.

Next, you need to consider the most effective way to address the problem. At this point, it is useful to consider multiple approaches. Organizations working on these problems generally need more policy analysts, researchers, operations staff, and managers. But you might also consider more unconventional options.

80,000 Hours also provides a set of tools to help people make decisions, and seek out especially promising career opportunities to share on their job board.

READ 80,000 HOURS’ CAREER ADVICE

One of the easiest ways that a person can make a difference is by donating money to organisations that work on some of the most important causes. Monetary donations allow effective organisations to do more good things, and are much more flexible than time donations (like volunteering).

Many people don’t realise just how rich they are in relative terms. People earning professional salaries in high-income countries are normally in the top 5% of global incomes. This relative wealth presents an enormous opportunity to do good if used effectively (You can get an estimate of your own relative wealth using this calculator).

How to give

There’s already a growing community of people who take these ideas seriously, and are putting them into action. Since 2009, thousands and thousands of people have taken the 10% pledge. Hundreds of people have made high-impact career plan changes on the basis of effective altruism. And there are hundreds of community groups for people interested in effective altruism, with dozens of these being in the Netherlands.

Read more Read less

Do you want to keep up to date with everything we’re doing? The best way to do so is by signing up for our monthly newsletter!